Changes in Alpine swifts' body size and shape

Art by Martina Cadin

Art by Martina Cadin

Effects of climate change on adult body size: Towards an integrative approach to understand the underlying mechanisms, the consequences across the lifespan, and improve our predictive ability

Funding: This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant agreement No 101025938, project name CLIMGROWTH. Link to the official page official page

Background

Changes in adult body size have become a flagship response to climate change. In organisms with a finite growth, as mammals and birds (higher vertebrates), it is thought to result foremost from climate-induced changes in growth trajectories (plasticity) rather than from changes in the frequency of alleles coding for body size (microevolution). As a key ecological trait, body size is also an important driver of individual life history: individual growth conditions will ultimately determine maturation, reproduction and ageing. However, to date no studies on higher vertebrates have formally investigated the contribution of developmental plasticity vs. microevolution at explaining changes in adult body size in response to climate change and, more importantly, no studies have tested for lifelong effects of climate-induced change in growth and size on individual life history within and between generations.

Methods and Aims

In my project, I propose to focus on the Alpine swift (Tachymarptis melba), a species of outstanding morphological and metabolic characteristics (non-stop flights of up to 200 days), for which preliminary results show a significant increase in body size. In particular, I will use an unprecedented long-term database (>4000 individuals, >20 years, collected by Dr. Pierre Bize) to combine complex, state-of-the-art, statistical modelling approaches in order to address these knowledge gaps by:

- testing for the first time in a higher vertebrate the contribution of developmental plasticity and microevolution at accounting for a change in body size using pedigree-based quantitative genetic models;

- providing long-awaited results on the lifelong consequences of natal climatic conditions on individual life histories;

- testing their transgenerational effects on offspring life histories;

- addressing the debate between quantitative geneticists and demographers in how to generate reliable predictions for responses to climate change by applying the different approaches in the same study system.

Results

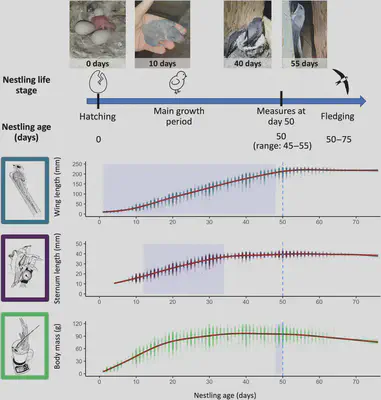

Trait-specific sensitive developmental windows: Wing growth best integrates weather conditions encountered throughout the development of nestling Alpine swifts

LINK: https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.11491

by Giulia Masoero, Michela N. Dumas, Julien G. A. Martin, Pierre Bize

Using measures for 3 morphological traits (wing length, sternum length, body mass) in Alpine swift nestlings, we found that:

- Sensitive developmental windows for wing and sternum length corresponded to the periods of trait-specific peak growth, which span almost the whole developmental period for wings and the first half for the sternum.

- Adverse weather conditions during these periods slowed down growth and reduced size.

- Although nestling body mass at 50 days showed the greatest inter-individual variation, this was explained by weather in the two days before measurement rather than during peak growth.Interestingly, the relationship between temperature and body mass was not linear, and the initial sharp increase in body mass associated with the increase in temperature was followed by a moderate drop on hot days, likely linked to heat stress.

- Nestlings experiencing adverse weather conditions during wing growth had lower survival rates up to fledging and fledged at later ages, presumably to compensate for slower wing growth.

Overall, our results suggest that measures of feather growth and, to some extent, skeletal growth best capture the consequences of adverse weather conditions throughout the whole development of offspring, while body mass better reflects the short, instantaneous effects of weather conditions on their body reserves (i.e. energy depletion vs. storage in unfavourable vs. favourable conditions).

Some photos from the fieldwork

A video of one of our colonies in Solothurn

Collaborators

Dr. Pierre Bize, Swiss Ornithological Institute, Switzerland

Prof. Julien Martin, University of Ottawa, Canada. Research group website.

Michela Dumas, University of Ottawa, Canada